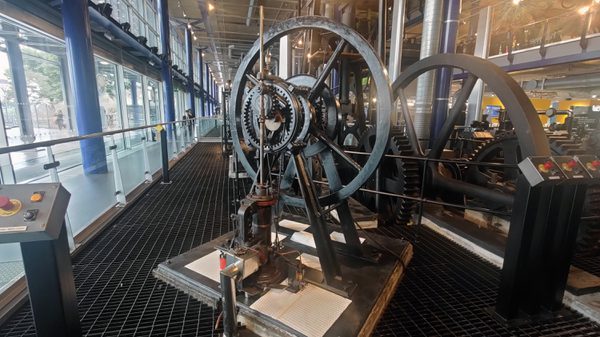

Iron Foundry Engine, c1805

Facts and Figures

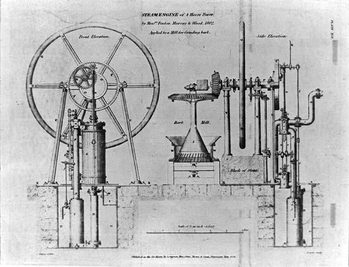

- Manufacturer: Fenton, Murray and Wood, Holbeck, Leeds

- Date built: c1805

- User: John Bradley and Co (Stourbridge Ltd), cl 805—1931. N. Hingley and Sons (Netherton Ltd), 1931-1961

- Period of use: c1805-1931

- Location: Stourbridge

- Engine type: Hypercycloidal straight-line motion engine

- Power output: 2 horsepower / 1.5 kilowatts

Introduction

This engine is the third oldest working steam engine in the world. It was used between 1805 and 1931 to drive a few machines in a small workshop in John Bradley's iron foundry in Stourbridge. Beam engines like the Smethwick Engine were very expensive and owners of smaller factories and workshops could not afford them. This type of engine was much cheaper and easier to install. Matthew Murray, who designed the engine, was one of the most innovative engine makers of his day. There are only two engines of this type left in the world.

History

Matthew Murray designed this unusual engine in 1802 when he recognised the need for a cheap engine for small factories. Beam engines were supplied in parts and assembled on site, which was a lengthy and expensive process. This engine's unique gearing system enabled the up and down motion of the piston to be converted into the rotary motion necessary to run machinery. By replacing the beam, the engine was very compact and made steam power more flexible. With Murray's skill and inventiveness, the firm of Fenton, Murray and Wood of Leeds became a major rival to Boulton and Watt.

John Bradley established his famous foundry and rolling mill beside the Stourbridge Canal in 1798. He soon achieved a reputation for producing high-grade iron. The engine was employed for 125 years in Bradley's iron foundry. Before the First World War it powered a few machines in a workshop. From 1931 it was displayed at Hingley and Sons factory in Netherton, where it was operated for the benefit of visitors until 1961.

In the first half of the nineteenth century, the Black Country became the biggest iron producing area in Britain. By 1857 there were over 150 furnaces in use making 650,000 tonnes of pig iron annually. The whole country saw a severe slump in iron manufacture between 1875 and 1886. For the Black Country this marked a permanent decline and by 1890 its iron output had fallen by two-thirds. When Bradley's closed in 1982 it was the last hand-operated rolling mill in the area. At one time there had been more than 300.

What's Special