The Science behind the Staffordshire Hoard

ResourcesA large-scale conservation and research project into the Staffordshire Hoard was launched in 2010, by Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery and The Potteries Museum and Art Gallery, Stoke-on-Trent.

The two museums have been working together to enable archaeologists, scientists, historians and curators from across the UK and Europe to carry out specialist scientific analysis, investigative cleaning and X-ray photography of these amazing finds. The ground-breaking work has uncovered internationally-significant results that link us to an age of warrior splendour and is increasing our knowledge of 7th century Anglo-Saxon England.

Uncovering the Staffordshire Hoard:

The hoard is a complicated collection because it is made up of lots of objects, mainly swords, that were torn apart before they were buried. This has made the conservation process similar to tackling a giant jigsaw puzzle with 4000 fragments.

When it arrived at the museum, the hoard was covered in lots of soil from the farmer’s field where it was found. Before the experts could research the objects, it was the conservation team’s job to remove the soil and reveal what lay underneath.

Once the objects were cleaned, it was also the conservators’ task to identify fragments from the same object; so far they have re-joined many objects back together, some from as many as 27 fragments.

X-rays:

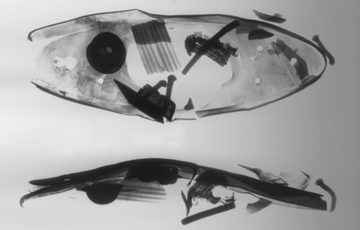

X-rays were taken of all the objects to help conservators see what was underneath the soil or inside the objects, just like at the hospital if the doctor thinks you may have broken a bone.

An X-ray can help determine the best way to conserve the object, help understand how it was made and whether it is broken or deteriorated. It is also a useful tool in evaluating authenticity and whether parts were added later.

Image gallery

How was the Staffordshire Hoard cleaned?

The conservators cleaned the hoard objects very carefully to ensure they were not damaged during cleaning and they recorded technical information about the objects. The conservators were in a very privileged position because they were the first people to see some of the objects for 1400 years.

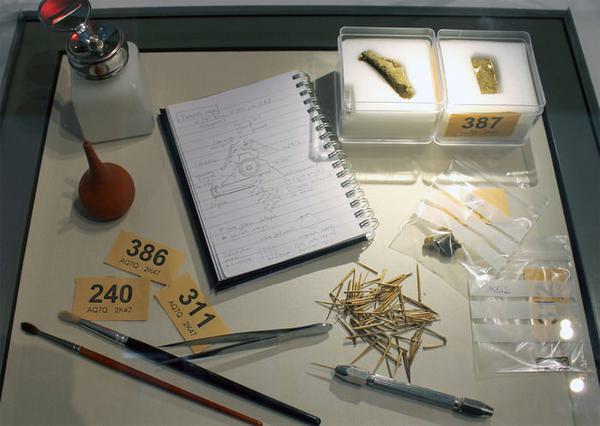

To remove the soil and clean the objects, conservators used the following tools:

- Microscope - to ensure object aren't damaged, conservators used microscopes to help them see all the tiny details.

- Brushes - these gently brushed loose soil off the surface of the objects.

- Plant thorn in a pin vice - the hoard was cleaned with berberis thorns, just like you would find in your garden. They have naturally very sharp points so can clean the delicate gold detail.

- Cotton wool - this was used to apply the solvent, ensuring that conservators do not put too much liquid on the objects as it may cause corrosion.

- Solvent / distilled water - solvents such as water and acetone were used to soften the soil, ensuring it was soft enough to be gently removed.

- Rubber puff - the puff is filled with air and when it is pressed the air comes out removing any loose soil.

- Notebook to record information - Conservators used notebooks to record everything they did to an object. It is important to document the process so people can find out what was done to the object in the future.

- Raffle Tickets for labelling - The raffle tickets were used during the initial documentation phase to ensure every object was given a unique number.

- Plasterzote ™ foam - this protects the object from any vibration as they are moved around for research. It also provides a cushion to support the objects which are fragile.

- Tweezers - are used to pick up very small fragments in the soil, as sometimes there were small gold or silver fragments within the soil that we need to keep.

Watch the following two videos to see Staffordshire Hoard objects being cleaned by conservators.

In this video Lizzie Miller, Objects Conservator, is cleaning the last of the Staffordshire Hoard objects, see her discuss how to clean a delicate gold and garnet object with thorns.

This video briefly shows a damaged Hilt Plate being cleaned and conserved using the tools that the hoard conservators use daily to remove soil and reveal the details of the pieces. The footage is from a camera that was attached to a microscope at a magnification of 7.50x.

What happened to the soil?

All the soil from the cleaning has been kept by the museum. This is in case new scientific techniques are developed in the future that may be able to tell us more information about the hoard by analysing the soil.

What is the Staffordshire Hoard Made From?

The objects in the Staffordshire Hoard are made of several main materials. Researching these materials allows us to understand how the hoard was made and gain insight into the skills of the 7th century craftsmen who made the objects. Investigating where the materials were sourced from also helps us to build a better picture of Anglo-Saxon people, their society and the world that they lived in.

Gold:

The majority of the objects are made of gold. Gold survives well when it is buried because it is very stable and does not corrode like other metals such as iron. This means that the hoard objects have remained remarkably unchanged and we can see all the intricate details and designs created in the 7th century.

Although the quality of the gold used in the hoard is very high, it is not totally pure. It also contains small amounts of impurities of copper, silver and platinum. This affects the colour of the objects, as the impurities can cause them to tarnish and darken over time.

Is it solid gold?

Scientific analysis tells us that the Anglo-Saxon goldsmiths managed to change the surface of the objects to remove some of the silver. This has the effect of making the object look even more golden. This technique is not understood fully but it seems that the goldsmiths used it to enhance their designs or to ‘colour match’ components when making repairs or replacements to an object. This shows us that the goldsmiths had a very sophisticated understanding of materials and technology. We don’t believe that they did this to fool the elite warriors into thinking that it was a higher quality gold.

Where does the gold come from?

We have tried to determine the source of the gold using X-Ray Florescence and Scanning Electron Microscope analysis, but it is likely that the gold used to make the objects in the hoard was recycled from older objects, weapon decorations or coins. No Anglo-Saxon gold mines have been identified.

Image gallery

Garnet

This semi-precious stone was used to decorate many pieces of the hoard. Garnets come in many different colours but the hoard only contains red ones. We are not sure why the Anglo-Saxons liked using garnets in their art but it was a style found all over Europe from the 5th century AD. So far we have counted over 3500 individually cut and mounted garnets in the hoard.

There are two sources of garnet in the hoard. The very small garnets came from the Czech Republic and the larger cut garnets are from the Indian subcontinent. Although this seems very far away, trade routes by boat and land across Europe and Asia were well established from the Roman period onwards.

One big question that we still don’t know the answer for is how they cut the garnets.

Image gallery

Silver

There are approximately 150 objects in the hoard made from silver. All but one of these objects were originally gilded to give them a gold appearance. Unlike the gold, the silver objects have become brittle while they were buried in the ground, this is due to the instability of silver.

We do not know the source of the silver, but there were known silver mines in Britain and Europe during this period. The craftsmen could also have been recycling older silver objects.

The group of three very large silver pommels below, are special because they have two sword rings (the ‘lumps’ on each side) all other pommels found before like this only have one.

Image gallery

Glass

Small pieces of glass decorate some pieces of the hoard. They are all recycled from other objects.

Analysis at the British Museum showed that the craftsmen were using both Roman millefiori glass and Anglo-Saxon vessel glass in the hoard objects. The Romans were capable of making very stable glass which has survived being buried in the ground very well. Anglo-Saxon glass is not as stable and it shows decay that we call corrosion. One of the most interesting garnet pommel caps has been repaired with cut red glass:

Image gallery

Piecing the Objects Back Together:

Project Archaeologists and Anglo-Saxon experts have been working with the conservation team to study every one of the 4000 objects and fragments, to piece the objects back together.

The Helmet

We now know that the Hoard contains parts of a very high status helmet, which may have belonged to a king. Helmets of its kind are rare – the Staffordshire Hoard helmet is one of a very small number to be found from this period. Two reconstructions of the helmet have been created and are on public display at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery.

Take a look at some parts of the helmet that have been discovered so far and the reconstruction helmet:

Image gallery

Digital Reconstruction

While we can try to piece as many fragments back together as we can, it will never be possible to put them back to how they would have originally looked during the Anglo-Saxon period. But with the help of the conservation and research teams we are able to digitally reconstruct some of the key pieces to show how we think they would have looked.

We have digitally reconstructed some of the objects. The playlist contains 6 videos (click the menu on the right of the video to see all the videos).

The Staffordshire Hoard is owned by Birmingham and Stoke-on-Trent City Councils, and cared for on their behalf by Birmingham Museums Trust and The Potteries Museum & Art Gallery. It was acquired in 2010 with the generous support of the Art Fund and the National Heritage Memorial Fund, as well as public donations. It is currently undergoing one of the UK’s largest archaeological research projects, conducted by Barbican Research Associates on behalf of the owners and Historic England, who fund the project.

Related resource

Take a look at our 'Discovering the Staffordshire Hoard' resource.