The Space Vault Audio Guide

ThinktankThis audio guide accompanies The Space Vault Exhibition at Thinktank, which showcases one of the UK’s largest private collections of space artefacts from human space exploration.

The guide includes an overview plus 12 tracks, each linked to a display station in the exhibition.

Overview

Read the overview

Overview

Welcome to the Space Vault Exhibition - the largest private collection of artefacts from human space exploration currently on public display in the UK. Surrounded by a lunar landscape composed of photographs taken by the Apollo astronauts on the Moon, there are 12 chronological displays that tell the thrilling story of spaceflight above the Earth and to the moon, from the Apollo program and Soviet space era, to the Space Shuttle, International Space Station and SpaceX.

As well as exploring the nearly one hundred artefacts on display, do take part in your own ‘Mission: Space Vault’. Match close-up photos of the 10 objects that form the highlights of the Exhibition with the actual artefacts. Mission patches on the gallery walls will point you towards these objects. You will be looking for: an X-Ray of Neil Armstrong’s Apollo 11 spacesuit gloves; the original flight checklist that saved Apollo 13; actual lunar dust from the landing site of Apollo 15; part of the spacesuit of Commander Dave Scott that spent three days on the lunar surface; a cosmonaut glove worn on spacewalks outside the Mir space station, and two flight suits: ‘Jack’ our Apollo Lunar Lander test pilot and ‘Vlad’ our Soviet space plane pressure suit. Also look out for a thermal protection panel from a Space Shuttle, chard black with the soot of re-entry to the Earth; a working wristwatch that spent 183 days on the International Space Station; part of the nose cone of the first SpaceX Starship to reach the threshold of space; and finally, the astronaut test results that put Edwin ‘Buzz’ Aldrin on the surface of the Moon.

We hope you enjoy your visit ….and get ready …because a giant Saturn V rocket is scheduled for launch in 4 minutes.

Display Station 1:

Engineering the Moon

Read transcript 1

Display station number 1. Engineering the Moon. The Lunar Landing Research Vehicle.

Here we have the full archive collection of Colonel Emil 'Jack' Kluever . We have his flight suits, two flight helmets, manuals, reports and photographs. Jack was the only pilot to fly the NASA's Lunar Landing Research Vehicle LLRV number 2. This number 2 vehicle and its sister, earlier, LLRV1 were experimental aircraft designed to accurately simulate the behaviour of a lunar lander in 1/6th lunar gravity.

It was an early flyby wire aircraft. The LLRV2 with Jack inside made six flights at Edwards Air Force Base in early 1967. So that's two years before the launch of Apollo 11. The craft was then decommissioned for parts to build three Lunar Landing Training Vehicles, LLTVs, and it was an improvised version of the LLRV that was used by the Apollo astronauts at Houston's manned spacecraft centre to practice landing on the moon.

Neil Armstrong himself was one of the pilots of this vehicle, and emphasised the craft's importance. I quote “the Lunar Landing Training Vehicle or LLTV, proved to be an excellent simulator and was highly regarded by the Apollo lunar module crews as necessary for lunar landing preparation”.

Display Station 2:

Saturn V

Read transcript 2

Display station number 2. Saturn V.

Speaking in 2008, Frank Borman, commander of Apollo 8, the first spacecraft to circumnavigate the moon, reflected on the launch, and I quote, “The Saturn V is still the most powerful machine the man has ever devised. Twenty tons of fuel, a second, seven and a half million pounds of thrust. I think we were all surprised at how strong that thing was. It had two or three iffy missions before ours, but it was a piece of cake. It just worked beautifully. Unbelievable.”

Of course, Space X now has the Starship Rocket, which has more power than the Saturn V when combined with its heavy booster launch vehicle.

Now on display here is the Saturn V engine gimble console. It's a mission control console to monitor the outboard F-1 engines on the SIC (S-one-C), the first stage of the Saturn V and the SII (”S-two”) second stage. Cathode ray tubes display the affiliated x, y hydraulic actuator deflections and the switches to monitor engine pitch and yaw. This console indicated degree of gimbaling, either change in the angle of orientation of the four outer engines on both Saturn V first and second stages.

Note that the fifth engine of the stage did not gimble. Gimbaling allows the application of directional thrust to keep the rocket on its true trajectory and a way to illustrate this is next time you're playing pool or snooker is try to balance the cue on your finger. You'll see it just tips over. However, if you just slightly move your finger left, right, back forwards, you'll be able to keep that cue moving upwards as if it was a rocket.

Display Station 3:

Apollo 9 - A Test Pilot’s Dream

Read transcript 3

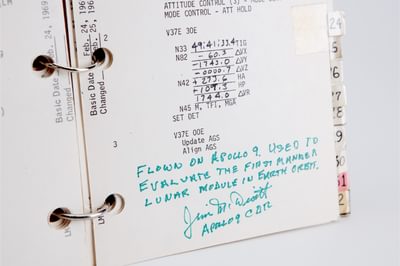

Display station number 3. Apollo 9, A Test Pilots Dream.

A ten day Flight of Apollo 9 in March 1969 was a test pilots dream mission. Swap with the Apollo 8 mission, which carried the first humans into lunar orbit and home safely to earth. Apollo 9 was the first and only low earth orbital mission to test the flight systems for the full stack of Saturn V Rocket, Command and Service Module, Lunar Module and Personal Life Support Systems Spacesuit. The collection of systems evaluation manuals used by Jim McDivitt, Rusty Schweickart and Dave Scott in space to evaluate the Apollo 9 systems are some of the most heavily annotated flown checklists from any mission in the history of human spaceflight. And we have one of those manuals in the exhibition. Here is the Lunar Module Systems Evaluation Checklist. And the pages are open at the all important test of the burn of the lunar module descent engine, while docked to the command module.

McDivitt is quoted as saying “This kind of operation might be required in case of a malfunction of the service module engine as we break into lunar orbit, we would then employ the descent engine on the lunar module to bring us safely home to Earth.”

And this is exactly what happened one year later on Apollo 13.

Display Station 4:

Apollo 11 - I’m Going to Step off the LEM Now

Read transcript 4

Display station 4. Apollo 11. I'm going to step off the LEM now.

Those were the first words ever spoken by human outside of a spacecraft on another celestial body. They were spoken by Neil Armstrong, and soon afterwards he stepped onto the moon, saying, “This is one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind”.

Now there’s three artefacts to look out for relating to this display station. You'll find a x-ray of Neil Armstrong's gloves lit up somewhere in the exhibition. What they were looking for were these x-rays, which were taken just before launch, were to see if there were any sharp objects, particularly needles, left inside the hand-sewn gloves, prior to launch in case on the lunar surface, they punctured the glove and caused the spacesuit to depressurise.

You'll also see two pages from a manuscript owned by Norm Carlson. Now, Norm Carlson was NASA's lead launch vehicle test conductor. That meant he controlled the countdown. And listening to audio archive from NASA. I'll quote some back to you here. You can hear the commentators saying “4 minutes, 15 seconds and counting”. This is until the Saturn V takes off. The test supervisor has informed the launch vehicle test conductor Norm Carlson, “You are go for launch”. From this time down, Carlson handles a countdown as the launch field begins its build up. And his call sign, Carlson, was CLTV and you can see that written on the manuscript, and he's checking off that he's done his steps along the way, on that document.

We also have, new to the exhibition, a part of the command module from Apollo 11. So as it orbited the moon with Mike Collins aboard that strip of Captain Foil, that was the thermal protection material, was on the command module, came back to Earth and is now part of the exhibition.

Display Station 5:

Apollo 13 - NASA’s Finest Hour

Read transcript 5

Display station number 5. Apollo 13, NASA's Finest Hour.

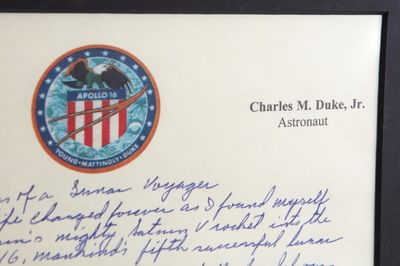

On April 13th, 1970, 55 hours and 54 minutes after launch, and 4/5th of the way to the moon oxygen tank 2 on Apollo 13 exploded. The incident threatened the life support systems in the command module, forcing the crew to conduct an emergency power down and retreat to the attached lunar module for use as a makeshift lifeboat. Thousands of NASA contractors jumped to the call, hastily improvising procedures for engineers at Mission Control to test in simulators and pass the solutions to the capsule communicator. By convention, this CapCom was a member of the backup crew trusted to act as the single point of communication between the crew and the whole of NASA. Charlie Duke was CapCom at the desk during parts of the Apollo 13 mission and tasked with reading up from his annotated Lunar Module contingency checklist procedures for critical burns and craft reorientations that brought the astronauts home to Earth. Artefacts on display include this contingency manual and others tell the rest of the story of how the Apollo 13 were rescued, what flight director Gene Kranz famously called "NASA's Finest Hour".

Display Station 6:

Apollo 15 - Life, The Universe and Everything

Read transcript 6

Display station number 6. Apollo 15, Life, the Universe and Everything.

Well, that's a quote from Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy and we use it here to describe Apollo 15, which was one of the ‘J’ missions of the Apollo program. These ‘J’ missions, the last three missions to the moon, were all about the science and the geology of the lunar surface.

There are two artefacts in the exhibition which have both spent time on the lunar surface. Dave Scott's lunar surface spacesuits communications umbilical cord, can be seen in a life sized image of Dave Scott in the exhibition and under his left arm you can see that cord hanging down. That is the communications umbilical through which he spoke as he stepped off the ladder for the first time and through which he communicated as he spent three days on the lunar surface.

We also have a sample of lunar dust from the Hadley Apennine region of the moon. This is dust that had collected in Dave Scott's personal kit bag, and it had come from the carrying of dust on the spacesuits back to the lunar module. And when they doffed their suits, the dust impregnated various items in the lunar module, including this kit bag.

Display Station 7:

Apollo 17 - A Geologist in Space

Read transcript 7

Display station number 7. Apollo 17. A geologist in Space.

In 1972, working alongside Apollo 17, Commander Gene Cernan, Harrison 'Jack' Schmitt became the first scientist to walk on the moon. Together, they toiled for three days on another celestial body. They worked until their fingers bled, their suits were impregnated with dust and their bodies soaked in sweat. They covered 50 kilometres and stopped at nine sites to conduct experiments, dig trenches, drill soil cores, and gather, weigh and record 244 pounds of extra terrestrial rocks to bring back to Earth. At ‘Shorty Crater’ they discovered the famous 'orange soil' that so excited 'Jack' and fellow geologists back on Earth, and which decades later provided insights into the origin of water on Earth.

In the display, we have parts of a manual that spent three days in the lunar module on the moon's surface, and these offer a contingency procedure to ascent in case of the need for aborting the mission.

You can also see on the blackboard a map showing the location of this ‘Shorty Crater’ and this was flown in lunar orbit.

And we have the drill bits manufactured by Martin Marietta Corporation that were designed to drill for core samples on the lunar surface.

Apollo 17 was the last mission to the moon. These are the last words spoken by a human on the lunar surface. Cernan said, “...as we leave the moon at Taurus-Littrow, we leave as we came and, God willing, as we shall return: with peace and hope for all mankind”.

Display Station 8:

The Soviet Space Era

Read transcript 8

Display station number 8. The Soviet Space Era. Back in the USSR.

At the end of World War II, both the Soviets and the Americans repatriated German V-2 rocket technology and scientists to help promote their own space programs. The USSR stole a march and became the first to test an intercontinental ballistic missile and the first to launch a satellite Sputnik 1. They were also the first to place a human, in earth orbit, Yuri Gagarin, the first to send a woman into space 20 years ahead of the United States and the first to transport terrestrial beings in lunar orbit and return them to Earth in the form of two tortoises. However, the Soviets lost the race to the moon and turned their attention to low-Earth orbit Space Stations.

Salyut 7, was a military space station and part of this space station is in the exhibition. It’s one of the largest pieces of space debris ever to fall to earth and go to private auction. It comes from a Kosmos supply vessel that was part of the space station at the time that it disintegrated in the Earth's atmosphere. There was no crew on board, and most of the space station disintegrated as it descended to earth, apart that is, from the heat shield. And there was a heat shield because this cargo vessel was also designed to be a lifeboat in case it was needed to bring crews back. And as designed, the heat shield survived reentry.

We also have two sets of gloves used in space on spacewalks by cosmonauts, both in relation to the Mir space station. The right hand glove belonging to cosmonaut Nikolai Budarin is interesting because it was used on the first mission to repair the Mir space station after extremely dangerous, life threatening collision. And we would urge you to listen to the video that explains about this collision. It is quite dramatic.

There's also a pair of gloves used inside the Soyuz capsule on ascent and descent to the Mir space station. These have to be much more dexterous and you can see the rubber gloves poking out through the leather base which gives the dexterity that's needed. We have a Strizh pressure suit which was designed for the Buran space plane, the Russian equivalent of the space shuttle, and can be pumped up to a pressure of four bars. This suit could survive jettison from a depressurised cabin at Mach three and 30 kilometres altitude.

Display Station 9:

US Space Shuttle - Mother of all RFPs

Read transcript 9

Display station number 9. US Space Shuttle. Mother of all RFPs.

Eight months before Gene Cernan on Apollo 17 became the last man to step off the moon's surface, NASA's contractor, North American Rockwell, received the request for proposal RFP to bid the design and construction of five orbiter vehicles for the space shuttle program. North America won the tender, valued at $16 billion in today's prices, making it one of the most valuable and certainly the most exciting single lump sum contract in history.

And we have in the exhibition a copy of that RFP tender document. It's a fascinating document. It sets out all the performance requirements of a space shuttle program and then the bidders, the tenderers, had to make offers of the design details that would deliver on those specifications. Framed in a picture is the gantt chart showing, across time, how orbiter 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 would be designed and built and tested and flown. In fact, there was an Orbiter 6 as well, following the challenger disaster.

In the exhibition, there were also some examples of the O-rings, which were infamously part of the origin of that disaster.

There's a piece of the space shuttle that's been swapped out and replaced, and this is one that's come through Earth's atmosphere and has charring and scorching marks on it. And it's sat as a thermal layer of protection behind the most protective carbon, carbon reinforced edge of the wing and in front of the aluminium struts that made up the space shuttle wings. During the Columbia disaster it was this type of thermal protection that had to take the heat that came through the damaged wing components, but could only hold off that heating impact for so long, until eventually found its way through to melt the aluminium wing struts.

Display Station 10:

International Space Station

Read transcript 10

Display Station Number 10. International Space Station, Entente in Space.

Combining the expertise, cooperation and budgets of five international space agencies, the International Space Station, the ISS, has been in low-Earth orbit for nearly a quarter of a century, carrying out over 3000 experiments. The station orbits Earth every 90 minutes, requiring 75 to 90 kilowatts of power to sustain its life support, propulsion, experiments and communication systems. At an altitude of 400 kilometres the ISS orbits where the Earth's atmosphere still creates some drag, demanding periodic reboots to remain in orbit and to avoid, increasingly, space debris.

The exhibition includes the cosmonaut, Gennady Padalka’s Russian ‘Poljot’ wristwatch, which flew for 185 days aboard the International Space Station in 2004. Padalka holds the world record for the most time spent in space at 879 days over five separate missions, beginning with Mir Expedition 26, in 1998, and then as commander of the ISS Expedition 9. The wristwatch is a working timepiece, and you can watch it functioning in the display. It depicts five early Soviet satellites, including Sputnik, and the case is engraved on the back with Soyuz TMA 4, ISS 9, 2004. And there are images showing the watch on the ISS in orbit.

We also have a USS flag flown as part of the payload of a SpaceX Dragon flight in August 2021, and this was stowed in a specially designed container to fit into voids between samples on a materials experiment. During this period, NASA's launched a commercial payload for Estee Lauder, which was met with widespread public disapproval, leading to an end to the eligibility of this type of commercial payload that the flag was part of.

Display Station 11:

Commercialisation of Space

Read transcript 11

Display station number 11. Commercialisation of space.

“Rockets are hard”. This is a quote from Elon Musk of Space X, and we have in the display a flown aluminium fragment from the wreckage of Space X FR9 development prototype rocket of the Falcon 9. Now the Falcon 9 vertical landing reusable rocket has revolutionized the cost of accessing space. In 2022, this launch system passed the space shuttles record to become the US rocket with most launches in space history. And as at the end of 2023, the Falcon 9 was the only US rocket certified for transporting humans to the International Space Station. Following development and testing, the Falcon 9 entered operations and to date has a 99% success rate.

In April 2023, we saw the first launch of Space X's Starship Plus Super Heavy booster, and that launch succeeded in leaving the pad, but it exploded during a belly flop manoeuvre. It was in November 2023, the second integrated launch of Starship that saw the craft actually enter space. And in the display, you can see a thermal tile from the nosecone of this second integrated flight, Starship 25. Eventually it too disassembled, reentered the atmosphere and you can see charring on the thermal tile in the exhibition. This piece fell over the region of Puerto Rico and ended up being washed onto the beaches of Saint Martin and was found by Ron Parker, a famed Starship debris hunter.

Display Station 12:

Astronaut Performance - The Right Stuff

Read transcript 12

Display station number 12. Astronaut performance. The right stuff.

That, of course, is the title of Tom Wolfe's famous novel about test pilots becoming astronauts. Only 12 humans have ever walked on the lunar surface and only a further 12 have orbited the moon. US astronaut selection started with the Mercury Seven, followed by the next nine. All these would test pilots.

Gus Grissom, one of the Mercury Seven, is quoted as saying “We are picking test pilots because they have experience in dealing with new machines, unusual situations and being scared to death, yet reacting properly”. And that nicely sums up why it was test pilots that made up most of the original astronauts and the ones that flew to the moon.

In the exhibition, we have two performance records and this continuous assessment of astronauts was absolutely critical to their selection for crews to fly to the moon in the Apollo program.

We have two original officer effectiveness reports providing evidence of Edwin Buzz Aldrin selection for the first moon landing. In January 1965, assesses Neil Armstrong and Deke Slayton, chief of the Astronaut Office, rated Aldrin four out of five across a range of competencies. Then one year later, after Buzz had completed a contribution to the development of the Apollo program, through his participation in the Gemini series, Deke Slayton and now Scott Carpenter reassessed Buzz Aldrin and scored him five out of five across all competencies and you can see that on the document in the display. Evaluation states "that as pilots of Gemini 12, Aldrin contributed, not only to the development of the mission plan, but to its execution as well. The outstanding success of the extra curricular phase of this flight is a tribute to this officer's unique contribution and strengths and talents". And this is why one could argue that these two documents are what put Buzz Aldrin on the moon.

We also have a handwritten memo by John Young stating serious concerns with the design of the space shuttle pressure suit. He raises concern as underlined on the document, 'the changing suit design from 8 PSI to 4 PSI pressure introduces safety risks, with 4 PSI, necessitate taking 45 minutes of pre breathing’. John Young argues that high risk justifies high cost and mocks managers that they had introduced a new design criteria qualifying 4 PSI on the basis that 8 PSI limits ability to wiggle one's fingers. However, Young lost the argument and NASA managers won the day.