News Story

Birmingham’s digital pioneers to take centre stage at Makers and Machines exhibition

- Makers and Machines held in new Thinktank exhibition space

- Learn about coding, digital creativity and AI chatbots

- Chance to play classic arcade games and design textiles

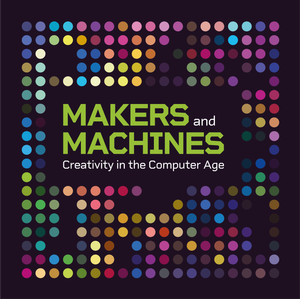

Programming Pioneers and Game Changers will take centre stage at a new exhibition called Makers and Machines: creativity in the computer age, at Thinktank, Birmingham Science Museum.

Opening on Saturday, July 22, the interactive exhibition will be held in a new space created on Level 2 of Thinktank at Millennium Point. Both the new exhibition space and Makers and Machines have been funded by Millennium Point Trust.

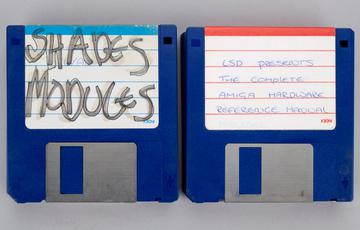

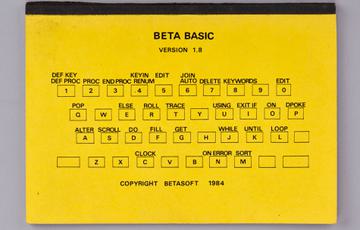

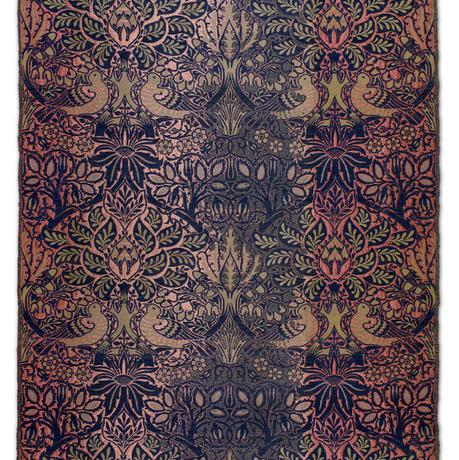

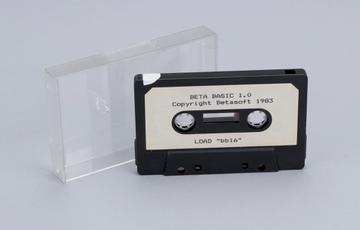

Makers and Machines will feature a range of digital and analogue devices, offer visitors a chance to play 1980s computer games, learn how to code on punched cards, and design their own weaving pattern.

Coding means writing instructions in a language that computers can understand and carry out. We think of this as a modern skill developed for the tech industry. But people have been trying to programme machines for hundreds of years, long before the invention of the computer as we know it and the exhibition will surprise visitors with the long history of coding.

Makers and Machines will show some of the diversity of local people and industries who use coding skills in their work and highlight some incredibly creative people in the West Midlands, past and present.

Among them Dame Stephanie Shirley, who grew up in the West Midlands after arriving in the UK in 1939 as an unaccompanied five-year-old refugee on the Kindertransport. A talented mathematician, Dame Stephanie set up her own software company, Freelance Programmers, in 1961. It was innovative in many ways, not least the idea of selling coding skills at a time when software was given away for free with computers. She also recruited only professionally qualified women who had to leave traditional employment as a result of caregiving responsibilities, offering flexible home working and job share contracts long before such working practices became commonplace.

Visitors will also meet weavers and knitters; mathematicians and scientists; artists and gamers, to see how they have used coding in their work, from Victorian machines to the first computers to modern artificial intelligence.

Image gallery

There will also be the opportunity to see rare and important objects in Birmingham for the first time in many years.

A highlight of the exhibition is the HEC computer, one of the oldest surviving electronic computers in the world. It was built in 1951 to a design created by Andrew and Kathleen Booth. Kathleen, originally from Stourbridge, was a programming pioneer who invented the first assembly language (a type of programming language which closely resembles the binary machine code which computers can understand).

The HEC is a star of Birmingham’s internationally-significant collection of early British computers, and it is returning to the city from the National Museum of Computing in Bletchley, where it has been on long-term loan since 2015.

Makers and Machines will also encourage visitors to think about the implications of new technology such as AI for human creativity. Visitors will meet an AI co-curator and be invited to see if they can spot the three object labels in the exhibition which have been written by an AI chatbot rather than a human curator. They will be prompted to discuss whether they trust them more or less.

Image gallery

The Makers and Machines exhibition has been developed with the help of a range of local community, education and industry organisations, from consultation on content and events to the loan of objects for display, among them Birmingham City University, the Bloomsbury Hope Centre, Cash’s of Coventry, the Dorothy Parkes Centre and the Sophie Hayes Foundation.

Entry is included in the price of entry to Thinktank. Visitors do not need to pay extra to see the exhibition, or book a time slot. However visitors are encouraged to book ahead for Thinktank, especially over the summer holidays, which can get busy.